Flight 93 monument honors victims, volunteers of 911

Editor's Note: This article originally ran on the 10th anniversary of flight 93 and the Sept. 11, 2011. We reprint it this month in tribute to

the crew and passengers.

Some people are burdened by Fate, others are drawn to it. Donna Glessner found her new calling Sept, 11, 2011, when Flight 93 crashed three miles from her rural Pennsylvanian home.

Glessner was at home with her two children when she heard a loud explosion. Her home rattled as if gripped by the trembling hand of Hades. Windows rattled. Walls vibrated.

“I thought it was an earthquake,” Glessner recalled. “So I took my two children outside.”

What she saw made her jaw drop. An oily plume rose swiftly over nearby farmhouses. The morose pewter could be seen for miles in all directions on this sunny, calm morning.

The adjacent town of Shanksville collectively sprang to action. Like most small towns, Shanksville has a way of disseminating news faster than modern media.

Just after 10 a.m., sirens wailed from Main Street. The phone switchboard lit as residents chatted among themselves and coalesced around a plan of action. Somewhere in the center of that plan was Glessner’s brother-in-law, Terry Shaffer.

As chief of the volunteer fire department, Shaffer stands among the first to know when disaster strikes. He led a team of first responders who secured the crash site and looked for signs of life.

“He said a commercial airliner went down off of Lambertsville Road and there were no survivors,” Glessner said. “Like most Americans I was surprised and shocked by what happened.”

Glessner instinctively knew how to respond, without hesitation.

“I volunteered to help,” she said. “It’s what we do.”

By her own account Glessner was at a turning point in her life. Her daughters were teen-agers now and beginning to explore life on their own. Her husband, Karl, owned and operated a local hardware store. She was looking for a new vocation.

Hundreds of local and federal officials gathered at the scene and turned the fire department into a command center. Townsfolk brought food and refreshments, which were shuttled out to emergency crews.

Flight 93 crashed into a reclaimed strip mine off a single-lane dirt road. The site is surrounded by thick hemlock forests. Some 1,300 officials pored over smoldering wreckage and combed through surrounding forest. A backhoe clawed at the impact crater in search of the flight recorder box.

All the while people like Glessner continued to donate and distribute food, and beverages. When the investigation officially ended 13 days later, the site became a labor of love for people like Glessner.

She and other volunteers became known as “ambassadors.” They vowed to staff the site every day of the year, including weekends and holidays.

It was a solemn vigil. From 10 a.m. to late afternoon an ambassador would staff the site in two-hour shifts. Volunteers stood for hours in summer sun or sought shelter in their own vehicles.

Visitors continued to stream in from all over the world. They would ask questions, looking for a receptive ear for their own 911 memories.

“They would show up every day even in bitter winter,” Glessner said. “We helped them understand what happened and many times we just listened. It was very emotional.”

By 2003 the National Park Service erected a temporary “Welcome” shed. Visitors jotted their thoughts and prayers in a stack of logs that now reaches to the ceiling.

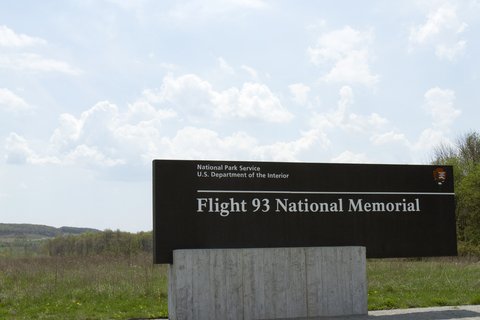

Three years later NPS officially recognized the ambassadors in 2006 and they continue to staff the recently dedicated Flight 93 National Memorial.

“The memorial is not only a story about Flight 93 but also about the community where it crashed,” said Jeff Reinbold, National Park Service site manager. “The airliner crashed in Middle America, and the site is a testimony to how a community came together to help.”

According to Reinbold, more than 70,000 donors have contributed to the memorial. There are also thousands of artifacts on display.

“It is very much of a ‘We the People’ exhibit,” Reinbold said. “Vistitors should not think of it as going to a site such as the Washington Monument. This experience is much more like going to Gettysburg.”

A newly paved road leads visitors off Lambertsville Road. The memorial encompasses 1,000 acres that have been preserved the way it was on the morning before the crash.

Memorial Plaza includes a prominent overlook of the site and a memorial wall to Flight 93 passengers and crew. Visitors are not allowed onto the crash site itself.

“Flight 93 National Memorial is very much an outdoor experience,” Reinbold said.

Reinbold suggested the following resources for visitors looking to research information about flight 93 and the Flight 93 National Memorial:

-

For general information on Flight 93 National Monument and directions, visit the National Park Service website at http://www.nps.gov/flni/index.htm.

-

To download a PDF file with details about passengers and the crew, go to http://www.nps.gov/flni/index.htm.

-

Get information about the inspiring flight 93 story at http://www.nps.gov/flni/historyculture/index.htm

-

Learn more about Shanksville, the little town that played an important role in preserving Flight 93 history. Visit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shanksville,_Pennsylvania.

-

For a live webcam on the memorial and information about archives go to: http://www.honorflight93.org/memorial/construction/?fa=live-webcam

-

-Interested in helping preserve Flight 93 National Monument and joining Friends of Flight 93? Go to http://www.nps.gov/flni/supportyourpark/index.htm.

- To read or submit Facebook comments about the memorial go http://www.facebook.com/honorflight93.

Article by Jay Alling, editor of Sensible Driver. Write to jay@sensibledriver.com.